Renaissance will be showcasing some of our innovative work at several events during this year’s annual Transportation Research Board (TRB) Annual Meeting.

The local foods movement has become a popular trend in recent years. Local foods can be defined as “food produced, processed, and distributed within a particular geographic boundary that consumers associate with their own community.” Simply put, the local foods movements seeks to better connect farmers with local consumers and vice versa. This is done through a number of different ways, including community gardens, farmers markets, food hubs, community kitchens, cooperative grocery stores, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), farm-to-school programs, farm-to-table restaurants, and many other ways. Over the last 14 years, the number of farmers markets in the country has nearly tripled and farm to school programs have grown from 6 in 2000 to over 4,000 in 2014. Some of the common motivators and benefits associated with buying local food include: supporting the local economy by keeping dollars local, environmental sustainability and the health benefits of buying and eating fresh foods. There are other less obvious motivators and benefits, such as the social connections and comradery created around growing and eating food with others based on a shared sense of community identity. Additionally, when local food activities like farmers markets, community gardens, and community kitchens are located along main streets and in downtowns - they can help support other place making goals such as improved walkability, downtown revitalization, community gathering spaces, and increased foot traffic for local retail.

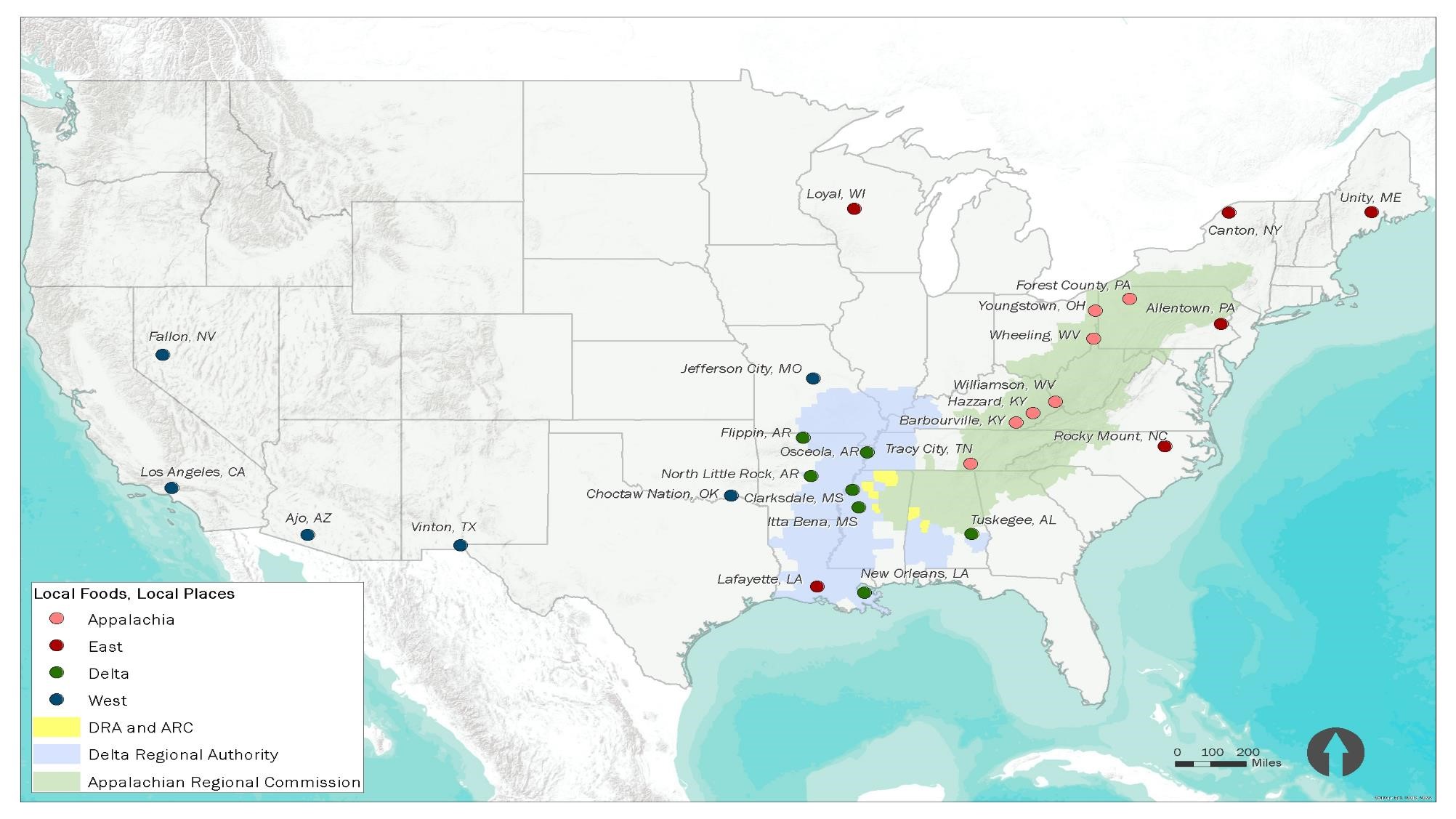

Local Foods, Local Places

The Local Foods, Local Places program is a unique partnership among the EPA, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), the Delta Regional Authority (DRA), and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that aims to help communities identify specific strategies and create a road map for achieving a range of placed-based, local food-oriented project goals. The community initiatives happening under this program range from building a community-owned cooperative grocery store in a small town on main street where people currently have to drive 10 miles to the nearest grocery store; to establishing a CSA in big city low income urban neighborhood that is currently a food dessert; to creating a food innovation hub seeking to foster food-based entrepreneurism in a redeveloping neighborhood, and many others.

The program is more than just about food. It is about bringing people together within these communities to devise creative ways for local food projects to enhance their neighborhoods, towns, cities and regions. The program synthesizes the goals of improved health, smart growth, economic revitalization, community development, and environmental sustainability through place-based food system projects.

Delivering the Goods

As a contractor to EPA, Renaissance is in the midst of delivering technical assistance to 26 communities across the country through the Local Foods, Local Places program. The technical assistance includes three key phases: issues identification, convening, and action planning. The focal point for the community is the on-site 1.5 day-long community and stakeholders workshop. This typically begins with a walking and windshield driving tour of the community to gather additional local insights and see first-hand some of the place-based issues and opportunities. The tour is followed by an evening meeting open to the public to talk about local community values, vision and goals. Day two usually includes interactive exercises with a focused group of stakeholders to map the local food system, discuss place-making opportunities, hear about best practices from other communities and identify pragmatic action steps to help the community start moving toward their local foods, local place goals.

I helped facilitate several of these workshops, all of them very different from one another, both in terms of the specific project the community was working on, and the geography and demographics of the place. Though these communities are different in many ways, many of them face similar inherent issues. They are losing population and suffering from a “brain drain”, their local economies are in decline or stagnant due to changes in industries (e.g. declining coal country economies), they are lacking a strong main street or thriving town center, and they are suffering from health-related issues partly due to a lack of access to healthy, fresh food.

In Itta Bena, Mississippi the small city of about 1,800 in the Mississippi Delta Region is in need of a grocery store because their only store closed about 10 years ago. Residents have to drive 12 miles to the next town over to get their groceries. For a low income community, this can be difficult when many do not own a car or are elderly and unable to drive.

Vinton, Texas is located just north of El Paso and the Mexico border. They want to start a community garden, farmers market, and small business incubator, but they lack the widespread local knowledge needed to grow their own food or start a new business. The community also lacks the funding and consensus needed to build water and sewer which is holding them back from economic development.

Idabel, OK is located in Choctaw Nation and near the borders of Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana and wants to expand their existing farmers market on their main street to include more growers and create more foot traffic downtown to support local retail. They also want to connect youth with aging populations who know how to farm and create value-added food products so that they can create a new generation of farmers and local food-related traditions that have been in families for centuries.

The Outcomes

In all of these workshops a common outcome is the creation of new connections between people in the community. The workshop often serves as a catalyst for action and helps bring people together around a common set of goals. With the additional federal interagency partners and other stakeholders involved, the workshops can also help to connect local communities with outside resources or organizations that can help them implement their local projects and action plans. This might include the identification of specific funding sources, additional technical resources, or the creation of new public private partnerships.

Williamson, WV was the recipient of technical assistance under the original Livable Communities in Appalachia program supported by EPA and ARC two years ago. At the time they were seeking help in strengthening their local food system and replicating their success in the surrounding region. We had the opportunity to go back to Williamson again this year to find them much further along in their local foods and placemaking efforts. They have a popular community garden and a farmers market that is in more demand than there is available supply. Their place-based focused efforts to concentrate activities in their traditional downtown continues to grow. Most recently they started a Federally Qualified Health Clinic, which is a free clinic located in downtown that has seen over 5,000 patients in just over a year of being open. The success of the clinic, the farmers market and community garden, and the huge number of people they now draw to downtown have sparked the opening of additional restaurants, some of which serve food grown from the community garden. Compared to our trip there two years ago, there is notably more activity in their downtown than there used to be.

This is the unique aspect of the local food programs. Co-locating these enterprises in downtowns and pairing them with other events can have a spin off effect on surrounding businesses. One community saw a 25% increase in downtown retail sales when the farmers market on their historic main street expanded to include music and art. There is a multiplier effect that happens when one of these initiatives, such as a farmers market, is successful. Momentum is generated, more initiatives are started based on the success of others and more benefits are seen.

I think we are only beginning to see how huge of an impact going local can have in helping communities to achieve their goals. Local food and local place initiatives can make a big impact not only in small, rural towns but cities of all sizes all over the country in helping to improve local economies, community cohesion, health, and positive environmental outcomes.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Appalachian Regional Commission, and U.S. Department of Agriculture will be kicking off a round of technical assistance to help small towns improve their residents’ access to locally-produced food. This effort includes the communities of Corbin, KY (of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame); Aberdeen, MS; Pikeville, TN; and Anniston, AL. Some of these communities are looking to launch a local food hub that makes it easier for institutions to purchase large quantities of produce from local growers, while others are looking to launch a farmers market or start community gardens in areas with poor access to grocery supermarkets.

These communities are far from alone. The number of farmers markets in the United States has more than doubled during the last 10 years and food is a growing area of interest among planners and elected officials. This interest reflects both a growing demand for local food and its role in supporting good public health and economic development.

2014 Farm Bill

Fortunately, in an era of declining public budgets, Congress has just given local food projects a substantial funding boost. In January Congress adopted a new Farm Bill after several years of debate. The national media attention has focused its coverage largely on farm subsidies and cuts to food stamps. But quietly, the Farm Bill increases financial support for local food systems by nearly 50 percent over the previous 2008 Farm Bill. Below are some of the highlights, with a big assist from the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition:

The Farm Bill more than triples funding for the Farmers Market and Local Food Promotion Program (From $33 million in the 2008 Farm Bill to $150 million in the new bill).

It quadruples funding for the Value Added Producer Grant Program (From $15 million to $63 million) that helps farmers increase their income through processing (for example, making jams and jellies out of fruit).

It more than doubles funding for the National Organic Cost Share Certification program, which helps farmers offset the cost of organic certification.

And it creates a new Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives program that will match SNAP benefits (food stamps) up to a certain dollar amount for purchases of healthy vegetables and fruits.

The increased funding for the Farmers Market and Local Food Promotion Program is especially important to the communities in Appalachia, many of which are working to create local food hubs that will aggregate products from multiple local farms and store, process, and distribute them to local consumers and institutions. It also brings good news for families and people who rely on SNAP benefits by increasing their buying power at farmers markets and even allowing them to use the benefits to participate in a community supported agriculture (CSA) program.

Breaking Down Silos

While the new Farm Bill provides more resources to support local initiatives around food, planners need to be involved to make sure these efforts realize their full potential for community development. As with transportation and land use planning, food planning has a tendency to exist in a silo, separate from other community efforts to improve transportation, housing, livability, economic development, and the many other areas where planners focus their attention. One key role planners can play is to help communities expand the conversation about how food systems planning and other community goals and objectives can overlap. By bringing in new voices that represent elected officials, businesses, community development, public health, social services and others, planners can help expand the discussion to integrate food systems planning into broader efforts to improve downtowns and neighborhoods and make them more livable places. Thinking carefully about where to locate local food hubs, markets, and other facilities is a key strategy for doing so. Ideally, the physical placement of these facilities can also support a community’s plans for economic revitalization and the creation of walkable town centers.

Those are just a few of my initial thoughts on the role that planners can and should play in food systems planning. Renaissance Planning Group will be serving as contractors to the U.S. EPA to deliver this technical assistance over the next several months. I hope to be able to share additional insights and highlight other lessons learned from that work through this blog.

-- Mike Callahan, Cities that Work Blog

What is Multimodal Planning?

Have you ever been frustrated because you can’t walk to a convenience store that is only a few hundred feet away away because there are no sidewalks? Or because your children can’t safely ride their bikes to a school located only a mile away? Many years of building roads without facilities for walking, biking and transit have made traveling by these modes a challenge. Communities throughout Virginia and the nation are realizing a desire to have more choices in how they travel.

Road diets, Complete Streets, Livability studies, streetscape improvements – these are all efforts within the planning profession to give people viable alternatives to driving alone. Transportation planning professionals use the term multimodal to describe anything that involves more than one mode of transportation, implying that there are more travel choices than just driving.

What are the benefits?

When communities invest in multimodal transportation improvements, they can experience a variety of benefits:

More transportation choices and streets that are often safer for all travelers.

Cost-efficiency - multimodal transportation investments focus on moving more people instead of more vehicles, and can make better use of the transportation facilities we already have instead of building new ones.

Reducing travel demand by autos, which in turn lessens congestion, lowers emissions, and improves air quality.

Addressing equity and social disparities by providing more travel choices for those with physical issues affecting mobility.

Encouraging more daily physical activity, and providing access to a wider range of goods and services.

Improving quality of life - streets can become places of social interaction and promote a greater sense of community pride.

Local governments throughout Virginia are increasingly making multimodal transportation investments a priority. They are enhancing sidewalks, creating bike lanes, and expanding transit service. They are developing bike plans and pedestrian plans to provide future connections. Some, such as the City of Roanoke have even developed and adopted design guidelines for multimodal streets.

A New Vision For Multimodal Planning in Virginia

To aid local governments in these efforts, the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation is developing the Multimodal System Design Guidelines – a holistic framework for multimodal planning at the regional, local and corridor scale.

The Guidelines provide a step-by-step manual of best practices for identifying centers of activity, designating connected networks for all travel modes, and designing and retrofitting multimodal corridors. Communities throughout Virginia can find these Guidelines helpful in planning for connected regional transportation networks that serve all travel modes.

Key Concepts in the Guidelines

There are a number of key concepts in the Guidelines, starting with the basic concept of a Multimodal System Plan. A Multimodal Systems Plan is an integrated land use and multimodal transportation plan that shows the key centers and corridors in a region and ensures that there is a connected circulation network for all travel modes. Typically, the development of a Multimodal Systems Plan is a mapping and analysis exercise that compiles existing plans and policies, rather than the establishment of a whole new policy framework. It assembles existing land use and transportation policies onto a single unified plan that serves as the basis for making decisions about more detailed multimodal planning at the scale of streets and centers.

The Guidelines also define Multimodal Centers as current or future centers of activity within a region where future growth may be targeted to provide a variety of destinations within walking distance. These centers are also where good travel options and well-connected street grids are present and where transit service may be provided. In particular, Multimodal Centers are areas that would most benefit from multimodal improvements, and, given limited transportation funds, may be target areas for multimodal investments. The Guidelines describe a series of seven Multimodal Center types, ranging from Urban Cores to Rural/Village Centers, with recommended standards, metrics and design features of each.

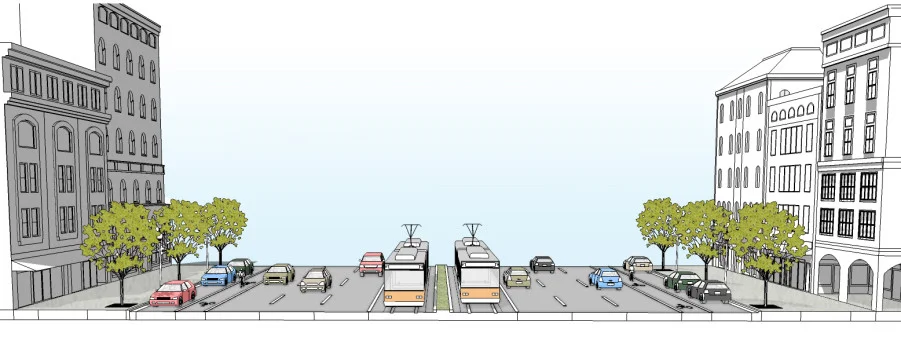

Finally, the Guidelines outline six types of Multimodal Corridors, ranging from Transit Boulevards to Local Streets. The design standards for the corridors are derived from industry standard publications such as the ITE/CNU’s “Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach. They are also correlated to the VDOT Road Design Manual, so that they meet or exceed all VDOT road standards. The Guidelines outline a flexible process for designing multimodal street cross sections based on Modal Emphasis. Modal Emphasis is the designation of one or more travel modes that should be emphasized in the design of the cross section for a given corridor, and is ultimately derived from the Multimodal System Plan. Modal Emphasis means that a travel mode may be emphasized on a corridor through certain design features but that other modes are still accommodated in some fashion.

This process of applying modal emphasis lets road designers customize a corridor for the specific needs of the emphasized modes, while still accommodating other travel modes, allowing the corridor to fulfill its function in the overall Multimodal Systems Plan.

Implementing the Guidelines

By planning comprehensively, from the Multimodal System Plan down to the design of each element of a corridor, the Guidelines can help ensure that the multimodal investments we make are the right projects in the right places, making it easier to walk, bike or take transit for our daily trips. One of the additional benefits of publishing and implementing the Multimodal System Design Guidelines is to start to standardize some of the planning language, concepts and best practices that are used throughout Virginia toward a more unified approach statewide. In the coming months, DRPT will be working with VDOT to implement the Guidelines by making them an optional set of standards for use in urban areas according to the Road Design Manual. The Guidelines are currently in a final draft form and can be reviewed on the DRPT website.

–Vlad Gavrilovic, Cities That Work Blog