Dan Hardy attended the ITE Annual Meeting in Toronto this year and writes up his thoughts and impressions from the proceedings.

Viewing entries in

Trends and Issues

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Appalachian Regional Commission, and U.S. Department of Agriculture will be kicking off a round of technical assistance to help small towns improve their residents’ access to locally-produced food. This effort includes the communities of Corbin, KY (of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame); Aberdeen, MS; Pikeville, TN; and Anniston, AL. Some of these communities are looking to launch a local food hub that makes it easier for institutions to purchase large quantities of produce from local growers, while others are looking to launch a farmers market or start community gardens in areas with poor access to grocery supermarkets.

These communities are far from alone. The number of farmers markets in the United States has more than doubled during the last 10 years and food is a growing area of interest among planners and elected officials. This interest reflects both a growing demand for local food and its role in supporting good public health and economic development.

2014 Farm Bill

Fortunately, in an era of declining public budgets, Congress has just given local food projects a substantial funding boost. In January Congress adopted a new Farm Bill after several years of debate. The national media attention has focused its coverage largely on farm subsidies and cuts to food stamps. But quietly, the Farm Bill increases financial support for local food systems by nearly 50 percent over the previous 2008 Farm Bill. Below are some of the highlights, with a big assist from the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition:

The Farm Bill more than triples funding for the Farmers Market and Local Food Promotion Program (From $33 million in the 2008 Farm Bill to $150 million in the new bill).

It quadruples funding for the Value Added Producer Grant Program (From $15 million to $63 million) that helps farmers increase their income through processing (for example, making jams and jellies out of fruit).

It more than doubles funding for the National Organic Cost Share Certification program, which helps farmers offset the cost of organic certification.

And it creates a new Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentives program that will match SNAP benefits (food stamps) up to a certain dollar amount for purchases of healthy vegetables and fruits.

The increased funding for the Farmers Market and Local Food Promotion Program is especially important to the communities in Appalachia, many of which are working to create local food hubs that will aggregate products from multiple local farms and store, process, and distribute them to local consumers and institutions. It also brings good news for families and people who rely on SNAP benefits by increasing their buying power at farmers markets and even allowing them to use the benefits to participate in a community supported agriculture (CSA) program.

Breaking Down Silos

While the new Farm Bill provides more resources to support local initiatives around food, planners need to be involved to make sure these efforts realize their full potential for community development. As with transportation and land use planning, food planning has a tendency to exist in a silo, separate from other community efforts to improve transportation, housing, livability, economic development, and the many other areas where planners focus their attention. One key role planners can play is to help communities expand the conversation about how food systems planning and other community goals and objectives can overlap. By bringing in new voices that represent elected officials, businesses, community development, public health, social services and others, planners can help expand the discussion to integrate food systems planning into broader efforts to improve downtowns and neighborhoods and make them more livable places. Thinking carefully about where to locate local food hubs, markets, and other facilities is a key strategy for doing so. Ideally, the physical placement of these facilities can also support a community’s plans for economic revitalization and the creation of walkable town centers.

Those are just a few of my initial thoughts on the role that planners can and should play in food systems planning. Renaissance Planning Group will be serving as contractors to the U.S. EPA to deliver this technical assistance over the next several months. I hope to be able to share additional insights and highlight other lessons learned from that work through this blog.

-- Mike Callahan, Cities that Work Blog

What is Multimodal Planning?

Have you ever been frustrated because you can’t walk to a convenience store that is only a few hundred feet away away because there are no sidewalks? Or because your children can’t safely ride their bikes to a school located only a mile away? Many years of building roads without facilities for walking, biking and transit have made traveling by these modes a challenge. Communities throughout Virginia and the nation are realizing a desire to have more choices in how they travel.

Road diets, Complete Streets, Livability studies, streetscape improvements – these are all efforts within the planning profession to give people viable alternatives to driving alone. Transportation planning professionals use the term multimodal to describe anything that involves more than one mode of transportation, implying that there are more travel choices than just driving.

What are the benefits?

When communities invest in multimodal transportation improvements, they can experience a variety of benefits:

More transportation choices and streets that are often safer for all travelers.

Cost-efficiency - multimodal transportation investments focus on moving more people instead of more vehicles, and can make better use of the transportation facilities we already have instead of building new ones.

Reducing travel demand by autos, which in turn lessens congestion, lowers emissions, and improves air quality.

Addressing equity and social disparities by providing more travel choices for those with physical issues affecting mobility.

Encouraging more daily physical activity, and providing access to a wider range of goods and services.

Improving quality of life - streets can become places of social interaction and promote a greater sense of community pride.

Local governments throughout Virginia are increasingly making multimodal transportation investments a priority. They are enhancing sidewalks, creating bike lanes, and expanding transit service. They are developing bike plans and pedestrian plans to provide future connections. Some, such as the City of Roanoke have even developed and adopted design guidelines for multimodal streets.

A New Vision For Multimodal Planning in Virginia

To aid local governments in these efforts, the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation is developing the Multimodal System Design Guidelines – a holistic framework for multimodal planning at the regional, local and corridor scale.

The Guidelines provide a step-by-step manual of best practices for identifying centers of activity, designating connected networks for all travel modes, and designing and retrofitting multimodal corridors. Communities throughout Virginia can find these Guidelines helpful in planning for connected regional transportation networks that serve all travel modes.

Key Concepts in the Guidelines

There are a number of key concepts in the Guidelines, starting with the basic concept of a Multimodal System Plan. A Multimodal Systems Plan is an integrated land use and multimodal transportation plan that shows the key centers and corridors in a region and ensures that there is a connected circulation network for all travel modes. Typically, the development of a Multimodal Systems Plan is a mapping and analysis exercise that compiles existing plans and policies, rather than the establishment of a whole new policy framework. It assembles existing land use and transportation policies onto a single unified plan that serves as the basis for making decisions about more detailed multimodal planning at the scale of streets and centers.

The Guidelines also define Multimodal Centers as current or future centers of activity within a region where future growth may be targeted to provide a variety of destinations within walking distance. These centers are also where good travel options and well-connected street grids are present and where transit service may be provided. In particular, Multimodal Centers are areas that would most benefit from multimodal improvements, and, given limited transportation funds, may be target areas for multimodal investments. The Guidelines describe a series of seven Multimodal Center types, ranging from Urban Cores to Rural/Village Centers, with recommended standards, metrics and design features of each.

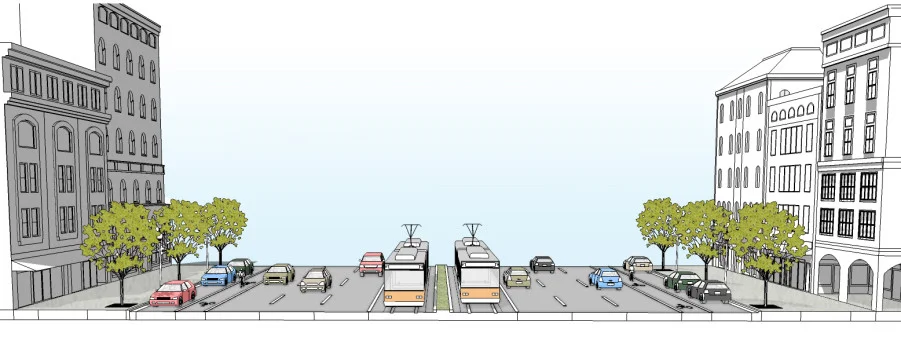

Finally, the Guidelines outline six types of Multimodal Corridors, ranging from Transit Boulevards to Local Streets. The design standards for the corridors are derived from industry standard publications such as the ITE/CNU’s “Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares: A Context Sensitive Approach. They are also correlated to the VDOT Road Design Manual, so that they meet or exceed all VDOT road standards. The Guidelines outline a flexible process for designing multimodal street cross sections based on Modal Emphasis. Modal Emphasis is the designation of one or more travel modes that should be emphasized in the design of the cross section for a given corridor, and is ultimately derived from the Multimodal System Plan. Modal Emphasis means that a travel mode may be emphasized on a corridor through certain design features but that other modes are still accommodated in some fashion.

This process of applying modal emphasis lets road designers customize a corridor for the specific needs of the emphasized modes, while still accommodating other travel modes, allowing the corridor to fulfill its function in the overall Multimodal Systems Plan.

Implementing the Guidelines

By planning comprehensively, from the Multimodal System Plan down to the design of each element of a corridor, the Guidelines can help ensure that the multimodal investments we make are the right projects in the right places, making it easier to walk, bike or take transit for our daily trips. One of the additional benefits of publishing and implementing the Multimodal System Design Guidelines is to start to standardize some of the planning language, concepts and best practices that are used throughout Virginia toward a more unified approach statewide. In the coming months, DRPT will be working with VDOT to implement the Guidelines by making them an optional set of standards for use in urban areas according to the Road Design Manual. The Guidelines are currently in a final draft form and can be reviewed on the DRPT website.

–Vlad Gavrilovic, Cities That Work Blog